The interim government’s ban on Bangladesh’s largest political party undermines democracy, empowers extremists, and threatens…

How the CIA and Their Local Progenies Assassinated Bangladesh’s Founding Father and Shook the World

Anwar A. Khan

The Carnage of 15 August 1975!

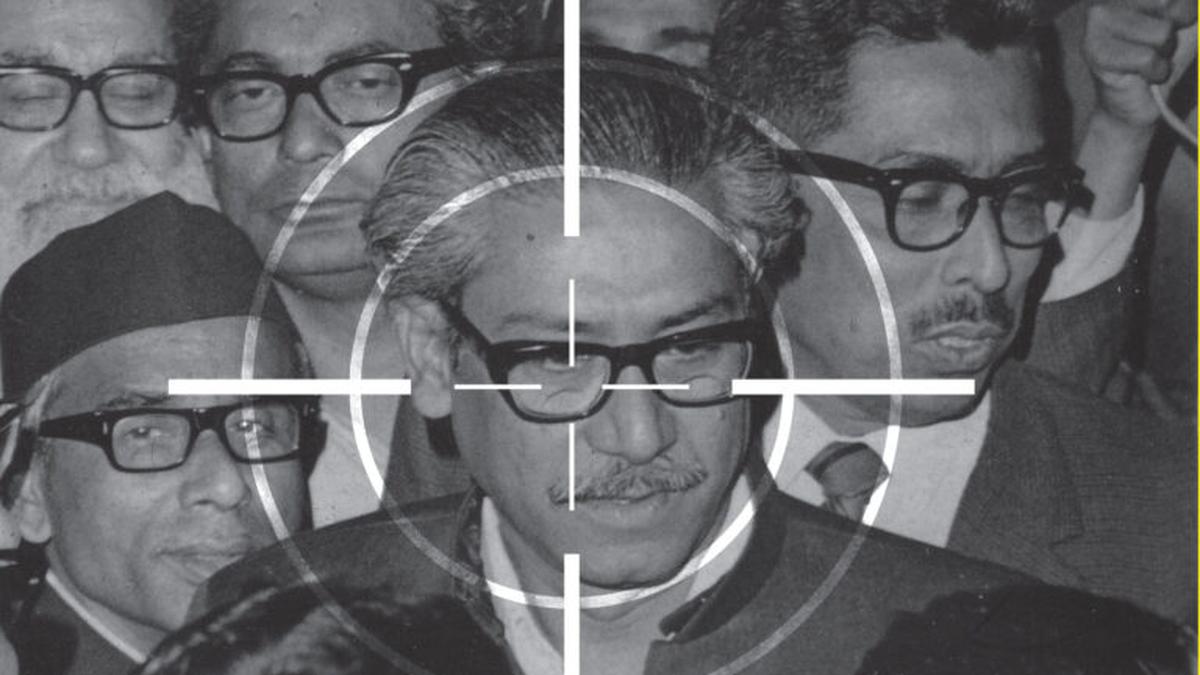

In the silent, ominous hours before dawn on 15 August 1975, the heart of Bangladesh was ripped out. The man who had birthed a nation through blood, sweat, and boundless courage—Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman—was brutally murdered alongside most of his family. This was no mere coup born of petty factionalism; it was a carefully choreographed act of political regicide, engineered by the CIA of the United States in collusion with local conspirators—political orphans, disgruntled Bangladesh army officers, and ideological heirs of the anti-liberation forces who had once sought to drown the Bengali dream in the rivers of 1971’s blood.

The carnage was both intimate and monumental. Mujib’s residence at 32 Dhanmondi was transformed into a slaughterhouse. Bullets riddled the body of the man who had led his people through the tempest of genocide to the dawn of freedom in 1971. His wife, Sheikh Fazilatunnesa Mujib—his lifelong companion in struggle—was gunned down. His sons, Sheikh Kamal, Sheikh Jamal, and the young Sheikh Russel, barely a child of age 10, were executed with cold efficiency. Daughters-in-law were slaughtered without mercy. This was not simply murder; it was a calculated attempt to erase an entire bloodline, to decapitate the moral and political leadership of Bangladesh in one fell swoop.

The shock reverberated far beyond Dhaka. Across the world, governments, liberation movements, and ordinary citizens recoiled at the barbarity. How could a people so recently emancipated be plunged into such darkness? The answer lay not merely in the treachery of a handful of soldiers, but in a web of international intrigue.

By the mid-1970s, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s foreign policy—anchored in non-alignment, economic self-reliance, and South–South solidarity—had made him a thorn in the side of Cold War strategists in Washington. He refused to be a pawn on the U.S. chessboard. His warmth towards India and the Soviet Union, his fierce defence of national sovereignty, and his outspoken criticism of imperialist interference made him a marked man. Bangladesh under Mujib had also begun rebuilding ties with socialist nations, opening trade doors with Cuba, and advocating for a New International Economic Order—policies that irked the architects of U.S. global hegemony.

The CIA’s fingerprints on political assassinations of the era are well documented—from Lumumba in the Congo to Allende in Chile. Bangladesh, barely four years old, became another stage for this ruthless doctrine. Declassified cables and historical testimonies point to American diplomatic circles maintaining close contact with disgruntled military officers, many of whom were ideologically aligned with Pakistan’s pro-Western, anti-communist elite. These officers, some trained in the United States, carried not only weapons but also the toxic conviction that Mujib’s Bangladesh had strayed too far from the orbit of Western control.

The local executioners were not random mutineers; they were ideological progenies of the defeated forces of 1971. Many were linked, directly or by affinity, to the political strands that had opposed Bangladesh’s independence—men who viewed the Liberation War of 1971 as a mistake and saw in Mujib an existential threat to their ambitions. The coup was their vindication, sanctioned and amplified by the CIA’s long shadow.

The aftermath was as chilling as the crime itself. Instead of national mourning, the state apparatus was swiftly commandeered to whitewash the assassinations. The infamous Indemnity Ordinance, promulgated by Khondaker Mostaq Ahmad—himself a usurper elevated to the presidency—shielded the killers from prosecution. The killers were rewarded with diplomatic postings abroad; their crimes laundered in the name of political “stability.” This was the kind of “order” foreign intelligence agencies favoured: pliant, malleable, and purged of inconvenient nationalist icons.

The moral inversion was complete. The very men who had betrayed the republic were feted as saviours. Political power shifted to an axis hostile to the spirit of 1971, an axis that reopened the space for Jamaat-e-Islami and other anti-liberation forces to re-enter the political bloodstream of Bangladesh. This was no accident—it was the structural realignment the conspirators, both foreign and domestic, had sought.

But even the most ruthless of assassins could not erase the truth of history. Mujibur Rahman’s legacy did not end on 15 August 1975. If anything, the brutality of that night immortalized him. His vision—of a secular, democratic, self-reliant Bangladesh—remained etched in the conscience of millions. The rivers he evoked in his speeches—the Padma, the Meghna, the Jamuna—continued to flow, carrying with them the undying current of the Bengali spirit.

Yet the cost was staggering. The coup derailed Bangladesh’s democratic experiment for decades, ushering in a cycle of military rule, political opportunism, and institutional corrosion. It emboldened those who saw politics as a commodity to be traded in foreign embassies rather than a sacred trust earned in the streets and fields. It planted the seeds for the periodic resurgence of communal and authoritarian forces, whose shadow still lingers.

Internationally, the assassination sent a chilling message: no leader, however beloved by his people, is beyond the reach of imperial power if he dares to defy its dictates. From Dhaka to Santiago, from Kinshasa to Tehran, the pattern was the same—covert destabilization, economic pressure, and when all else failed, assassination. The moral outrage voiced in the days following 15 August 1975 eventually faded, replaced by the cold calculus of realpolitik.

It took more than two decades, and the return of Sheikh Hasina—Mujib’s surviving daughter—to power, for the wheels of justice to turn. The Indemnity Ordinance was repealed, trials were held, and some of the assassins were executed. But justice delayed is justice diminished; too many died without facing the gallows, too many accomplices lived out their days in comfort abroad. The deeper conspiracies—the foreign fingerprints, the complicity of entire networks—remain, in part, beyond the reach of formal justice.

Remembering 15 August is therefore not a passive act of memorialization; it is a political necessity. It demands that we confront uncomfortable truths about the vulnerabilities of small nations in a predatory world order, about the ease with which local betrayals can be weaponized by foreign agendas. It calls for vigilance against the ideological heirs of those who pulled the trigger in 1975—those who still cloak their opportunism in the language of patriotism while serving masters beyond our borders.

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was not infallible; no statesman is. But his flaws were those of a man building a nation from the ruins of war, not those of a tyrant or a traitor. His assassination was not the verdict of history—it was the interruption of history. The architects of that interruption hoped that by destroying the man, they could extinguish the ideals he embodied. They failed.

On every 15 August, as the nation lowers its flags and bows its head, we are reminded that the price of freedom is eternal vigilance. We honour Mujib not by embalming him in rhetoric, but by defending the sovereignty, secularism, and unity he fought for. We reject the politics of subservience and betrayal that culminated in his murder. We assert, in defiance of both the conspirators of 1975 and their latter-day reincarnations, that Bangladesh’s destiny will be written by her people, not dictated from foreign capitals.

The world shook on 15 August 1975—not merely because a leader was killed, but because it laid bare a brutal truth: the liberation of a nation is never final. Independence can be won on the battlefield but lost in the shadows, to whispers in foreign chancelleries and the treachery of compatriots without a country in their hearts.

Bangabandhu’s blood cries out from the floors of Dhanmondi 32, not for vengeance alone, but for vigilance, courage, and unity. If we fail to heed that call, we risk living the nightmare of 1975 again—different actors, different pretexts, but the same betrayal.

Let the memory of that black dawn steel our resolve. Let the conspirators, wherever they hide—in history’s margins or in positions of present influence—know that Bangladesh remembers. And in remembering Bangabandhu, Bangladesh resists.

Anwar A. Khan is a freedom fighter based in Dhaka, Bangladesh. He writes on politics and international issues.

Comments (0)