In an era where change is broadcast live and justice is hashtagged, Generation Z has…

Contesting Liberation: Why the 2024 Movement is Not a Continuation of 1971

Prof. Dr. A K Lam & Prof. Dr. R Ris (Nick Names)

Introduction

In Bangladesh, the legacy of the 1971 Liberation War remains the moral and ideological foundation of political legitimacy—a sacred chapter in the nation’s history that continues to shape its identity and aspirations. It is against this deeply emotional backdrop that the architects and supporters of the 2024 movement against the government of former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina have deliberately framed their struggle as a continuation of that foundational spirit—a second wave of resistance in the long fight for democracy. Yet, upon closer examination, this comparison proves not only historically shallow but fundamentally misleading. While the language of liberation and revolution is powerfully evoked, the 2024 movement lacks the philosophical depth, legal grounding, and unifying national purpose that defined the struggle of 1971. This analysis rigorously contrasts the two movements through historical, legal, and ideological lenses, demonstrating that they are distinct phenomena—separated by their essential aims, their adherence to constitutional versus revolutionary legitimacy, and their vision for the nation. Where the Liberation War sought to create a state, the 2024 movement seeks to unseat a government. Where 1971 united a people against colonial subjugation, the current mobilization reflects deep—but domestic—political divisions. To conflate the two is not just an oversimplification: it risks diminishing the singular sanctity of the Liberation War while obscuring the true nature of today’s political contestation as a struggle for power within the framework of the state that 1971 made possible.

The core principles of the Liberation War:

The 1971 liberation war has the following core principles, which have made it omnipresent, comprehensive and sacred to all Bengali people.

Philosophical Underpinnings: Identity, Secularism, and Self-Determination

The Liberation War of Bangladesh was not merely a military or political conflict but a profound philosophical struggle centred on identity, autonomy, and the right to self-determination. At its core, the war represented the rejection of the Two-Nation Theory—the ideological foundation of Pakistan, which asserted that religious identity alone could define a nation. The people of East Bengal instead embraced a pluralistic, linguistic, and cultural nationalism, rooted in the Bengali language, secular traditions, and a shared history of cultural syncretism. This vision stood in direct opposition to the West Pakistani establishment’s efforts to impose a homogenized Islamic identity, which systematically marginalized Bengali culture, language, and political representation. The philosophical ethos of the liberation movement was encapsulated in Bangabondhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s historic speech on March 7, 1971, which called for emancipation from oppression and affirmed the Bengali people’s right to shape their own destiny. Scholars like Amartya Sen have argued that the conflict exemplified the dangers of reducing complex human identities to singular, rigid categories—a theme explored in his book Identity and Violence: The Illusion of Destiny. The war thus became a battle for the soul of a nation, striving to establish a society based on democracy, secularism, and social justice.

Legal Justifications: International Law, Self-Determination, and Accountability

From a legal perspective, Bangladesh’s struggle for independence was grounded in the fundamental principle of self-determination, a right enshrined in the United Nations Charter and international law of 1966. The Pakistani state’s refusal to honour the results of the 1970 general elections—in which the Awami League won a decisive majority—constituted a breach of democratic norms and provided legal and moral justification for secession. The subsequent military crackdown, launched through Operation Searchlight on March 25, 1971, involved widespread atrocities that amounted to genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes. These included the targeted killings of intellectuals, mass sexual violence, and the systematic destruction of villages and cultural institutions. International observers and jurists, such as those from the International Commission of Jurists, documented these violations, while diplomats like Archer Blood, the U.S. Consul General in Dhaka, explicitly condemned the actions of the Pakistani military in the famous Blood Telegram. The legal case for Bangladesh’s independence was further strengthened by the sheer scale of human suffering, which invoked the responsibility of the global community to intervene in cases of grave humanitarian crises. Although Pakistan’s actions were widely criticized, geopolitical considerations delayed full international recognition of Bangladesh until after its victory in December 1971.

Ground Realities: Suffering, Resistance, and Resilience

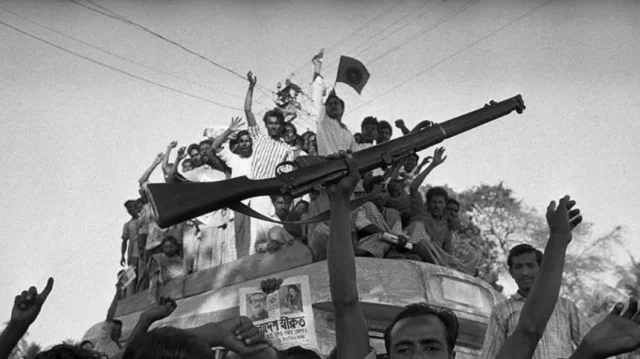

On the ground, the war was marked by extraordinary human suffering, collective resistance, and unparalleled resilience. An estimated three million people were killed, and over ten million refugees fled to India to escape violence and persecution. The Pakistani military and its auxiliary militias (such as Razakars) engaged in systematic campaigns of violence, including the targeted elimination of intellectuals, farmers, students, and religious minorities. Women were subjected to mass sexual violence, with estimates suggesting between 200,000 and 400,000 rapes—a strategy intended to terrorize and destabilize the social fabric of Bengali society. Despite this, the people of Bangladesh mounted a fierce and organized resistance through the Mukti Bahini (Liberation Forces), which included both civilian guerrillas and military defectors. Their efforts were complemented by international solidarity, particularly from India, which provided logistical support, refuge, and eventually direct military assistance. The war also witnessed the emergence of a vibrant cultural resistance, with artists, poets, and musicians using their work to inspire and unite people. Scholars like Nayanika Mookherjee have highlighted the long-term psychosocial impact of the violence, particularly on survivors of sexual assault, who were later honoured as Birangonas (war heroines) in an effort to reclaim their dignity and place in history. The conflict culminated in a decisive victory on December 16, 1971, when the Pakistani military surrendered in Dhaka, paving the way for the birth of an independent Bangladesh.

Scholarly Presentation of the Liberation War

The legacy of the Liberation War continues to be analyzed and interpreted by scholars across disciplines: Amartya Sen emphasizes the conflict’s significance in understanding identity-based violence and the necessity of pluralistic societies. Geoffrey Davis, an Australian physician, provided critical medical testimony and documentation of the atrocities, reinforcing claims of genocide and systematic sexual violence. Nayanika Mookherjee’s anthropological work, The Spectral Wound: Sexual Violence, Public Memories, and the Bangladesh War of 1971, explores the enduring trauma of survivors and the complexities of memory and justice.

The war remains a foundational narrative for Bangladesh, symbolizing the triumph of justice over oppression, unity over division, and hope over despair. Its principles of democracy, secularism, and human dignity continue to resonate in the national consciousness, even as the country grapples with the ongoing challenges of preserving this hard-won legacy. Authors and scholars termed this war as the war of independence of the Bengali nation, political emancipation and economic freedom that started with the creation of the Pakistan state.

2024 Political Movement:

The 2024 political movement against the Sheikh Hasina government in Bangladesh marked one of the most intense waves of public dissent in recent history, rooted in deepening political, economic, and civic grievances. What began as a student-led quota reform movement quickly escalated into a nationwide uprising, fueled by government mismanagement and mishandling of the protests. The movement’s momentum created space for multiple actors—both national and international—to leverage the unrest to challenge and destabilize the regime. Although the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) initially refrained from directly supporting the agitation, it sought to capitalize on the political crisis, while Jamaat-e-Islami and its student wing, Shibir, played a commanding role in mobilizing students and ordinary citizens. At its core, the movement demanded the government’s resignation, the installation of a neutral caretaker administration to guarantee free and fair elections, and immediate measures to address skyrocketing inflation, widespread unemployment, and entrenched corruption.

The protests were also an expression of growing frustration with what critics describe as authoritarian tendencies—ranging from the suppression of dissent and curbs on press freedom to the use of judicial and security apparatuses to sideline political opponents. The state’s response was characterized by arrests, allegations of excessive force, and internet blackouts, which drew sharp criticism from international human rights organizations. Economically, surging prices of essential goods and energy shortages further eroded public trust, while politically, the lack of a level playing field deepened polarization across the nation. The 2024 movement, therefore, was more than a response to immediate grievances; it reflected broader anxieties about democratic backsliding, accountability, and the erosion of participatory politics. How this crisis is resolved will profoundly shape Bangladesh’s trajectory—either paving the way for greater pluralism, inclusivity, and dialogue, or cementing a path toward further authoritarian consolidation.

The Claim: 2024 is a Continuation of 1971?

Proponents of this view, primarily the opposition and its supporters, frame the 2024 movement through the same ideological lens as the 1971 Liberation War. Their argument rests on these key points: The Same Foundational Struggle: They argue that both movements are fundamentally about the same principle: the fight for democracy, self-determination, and the people’s right to choose their own government. They claim that the 1971 war was fought to escape the authoritarian rule of West Pakistan, and the 2024 movement is a struggle to escape an authoritarian system that has developed within Bangladesh itself. The Same Spirit of Resistance: They draw a parallel between the spirit of the Bengali people in 1971, who rose against an oppressive military regime, and the spirit of the people in 2024 protesting against what they see as an oppressive, unelected government. The Same Adversarial Tactics: The opposition draws direct comparisons between the tactics of the Pakistani army in 1971 and the current government’s actions, alleging the use of: State-Sponsored Violence: Citing alleged enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings, and police brutality; Suppression of Speech: Highlighting the control of media and censorship of dissent; Denial of Democratic Rights: Equating the Pakistani regime’s refusal to hand over power after the 1970 election to the current government’s conduct in the 2014 and 2018 elections, which major opposition parties boycotted or alleged were rigged. Ideological Betrayal: A core argument is that the current government, led by the party of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (the leader of 1971), has betrayed the core principles of the Liberation War: secularism, democracy, and social justice. Therefore, the 2024 movement is framed as an effort to “reclaim the spirit of 1971. All these narratives have no philosophical or legal ground. Their supporter just resemble the past historical events of Bangladesh.

The Counter-Argument: Critical Differences

The assertion that the 2024 anti-government movement in Bangladesh is a direct continuation of the 1971 Liberation War is a powerful political narrative but lacks grounding in philosophical and legal reality. Philosophically, the 1971 war was an existential struggle for sovereignty and the creation of a new state, rooted in the rejection of the Two-Nation Theory and the assertion of a secular, linguistic Bengali identity against a foreign occupier (Pakistan). It was a unified national movement driven by the pursuit of self-determination and foundational principles like democracy and secularism, as reflected in the historic 1971 proclamation of independence. In contrast, the 2024 movement is an internal political contest within the established state of Bangladesh, focused on regime change, electoral fairness, and governance reforms. It operates within the domestic constitutional framework and does not seek secession or invoke a new national identity but rather demands the fulfillment of the existing state’s democratic promises (Ahmed, 2023; BBC, 2024).

Legally, the 1971 war was justified under international law through the right to self-determination, recognized by the United Nations Charter, and was precipitated by genocide and crimes against humanity perpetrated by the Pakistani military—a fact documented by international bodies like the International Commission of Jurists (1972) and witnesses such as Archer Blood (1971). The conflict resulted in the creation of a sovereign state. The 2024 movement, however, derives its legitimacy from domestic constitutional law, including the rights to assembly, expression, and electoral integrity under the Bangladesh Constitution. Its grievances—such as alleged electoral manipulation and suppression of dissent—are matters of internal governance and do not invoke international legal doctrines like secession or external self-determination (HRW, 2024; The Daily Star, 2024). Thus, there is no point in comparing with the 1971 liberation war.

While the 2024 movement rhetorically invokes the “spirit of 1971” to claim moral high ground and mobilize support, the two events are fundamentally distinct: one was a war of independence against a foreign power, and the other is a political movement of some sections of people for democratic accountability within a sovereign nation and to capture political power. After the removal of Sheikh Hasina, it has been proven that all the positions have been captured by the Jamat and BNP people without following any legal ground. It thus proved that they had the intention to capture political power and resources. The conflation of the two serves as a persuasive tool for opposition groups but overlooks the historical, philosophical, and legal chasm between them.

However, philosophically and legally, the two movements are categorically different. 1971 was an existential, anti-colonial war that created a state. 2024 is an internal, political struggle to determine who governs that state and how. Conflating the two, while rhetorically effective, overlooks their fundamentally distinct natures, goals, and places in the history and legal trajectory of Bangladesh. They argue that the two events are fundamentally different in nature, context, and objective.

| Feature | 1971 Liberation War | 2024 Anti-Government Movement |

| Nature & Goal | An armed struggle for independence and the creation of a sovereign state against a foreign occupying army. | A political movement within an existing sovereign state aiming for regime change and democratic reforms. |

| Adversary | The state of Pakistan and its military are a clearly defined foreign enemy. | The incumbent government of Bangladesh, a domestic political opponent. |

| Legal & Moral Basis | A fight for the right to self-determination, a fundamental principle of international law, in response to genocide and crimes against humanity. | A contest over electoral governance and political power within the constitutional framework of Bangladesh. |

| Unifying Identity | Unquestionably unified the Bengali populace (across most religions and classes) against a common foreign foe. Unity was absolute. | Deeply politically divisive. It is supported by one political bloc and opposed by another. There is no unified national consensus. |

| International Context | Fought during the Cold War; India provided direct military intervention and support; global opinion was largely sympathetic. | Occurs in a complex geopolitical context; international calls are primarily for dialogue and peaceful elections, not for supporting a secessionist movement. |

| Outcome Sought | Secession and the creation of a new nation (Bangladesh). | Reform of the existing nation (election integrity, democratic institutions, economic policy). |

Conclusion: A Powerful Narrative vs. Historical Reality

The claim that the 2024 movement is a continuation of 1971 is less a historical truth than a calculated political narrative. It serves as a powerful framing device for the opposition, allowing them to cloak their struggle in the sacred symbolism of the Liberation War—the nation’s most unifying founding myth. This rhetoric evokes a deep emotional resonance and conveys a sense of moral legitimacy. Yet, historically and legally, the two events remain fundamentally distinct. The 1971 Liberation War was an anti-colonial secessionist struggle against a foreign oppressor. By contrast, the 2024 movement is an internal political contest within a sovereign state, centred on questions of power, governance, and democratic accountability. This raises a central contradiction: how can a movement claim to embody the spirit of 1971 when it is led by forces that once opposed Bangladesh’s very existence? The Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP)’s longstanding alliance with Jamaat-e-Islami—a party directly complicit in atrocities during 1971, with several of its leaders convicted of war crimes—is not a minor political footnote but a profound moral paradox. To equate this coalition-led agitation with the Liberation War is, in essence, to distort history.

For the generation that sacrificed everything for independence, today’s unrest is not a continuation of their struggle but a betrayal of it. The very elements that once collaborated with occupying forces now seek to destabilize the sovereign state built through blood and sacrifice. As one freedom fighter defiantly remarked: “We fought against the Pakistani army and their Razakar collaborators. Now, the heirs of those Razakars torch the very nation we created. This is not politics—it is an assault on our independence itself.” Far from being a forward march toward democracy, the movement risks reopening old wounds and reviving ideologies that the Mukti Bahini fought to eradicate. It underscores the enduring challenge of protecting the legacy of 1971 against those who would exploit it for their own gain while undermining the sovereignty it delivered.

Reference:

Ahmed, S. (2023). The Unfinished Revolution: Democracy and Identity in Bangladesh. Academic Press.

Archer Blood (1971). The Blood Telegram: Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide. Knopf.

BBC (2024). “Bangladesh Protests: What’s Behind the Unrest?” BBC News.

HRW (2024). Human Rights Watch World Report: Bangladesh.

International Commission of Jurists (1972). The Events in Bangladesh: A Legal Study.

The Daily Star (2024). “The 2024 Movement: A Demand for Democratic Renewal.”

The Authors are Professors of a University

Comments (0)