The interim government’s ban on Bangladesh’s largest political party undermines democracy, empowers extremists, and threatens…

The Politics of Allegation: Unpacking the Money Laundering Narrative Against the Awami League

Dr. Mamunur Rashid

For over sixteen years, a systematic narrative has been woven to accuse the Awami League—Bangladesh’s longest-serving ruling party—of large-scale money laundering. This campaign intensified following the party’s fall from power on August 5, 2025. In the aftermath, renewed attempts have emerged to formalize these allegations through the publication of a white paper aimed at discrediting the previous government.

At the forefront of this narrative is Dr. Debapriya Bhattacharya, a Fellow at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD) and a known architect of the 1/11 political episode. He has asserted that from 2009 to 2023, Bangladesh saw an annual outflow of nearly $16 billion through illicit financial transfers. His claim rests on what he described as a “consultative process”—a vague methodological basis that has yet to be substantiated with verifiable data.

Nobel Laureate Dr. Muhammad Yunus has taken this further, suggesting to international media that the actual amount might be as high as $17 billion annually. However, even Iftekharuzzaman, Executive Director of Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB), has acknowledged that such allegations of corruption are “not entirely provable.”

Despite the lack of concrete evidence, these speculative figures have rapidly gained traction across global news outlets and social media. The result has been a dangerously sweeping campaign that targets not only former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and her immediate circle but also casts aspersions on the over 50 million citizens affiliated with or supportive of the Awami League. In some cases, the repercussions have already manifested in professional dismissals and public shaming.

This article seeks to examine the motivations, inconsistencies, and political strategy behind these claims and to explore the deeper implications of weaponizing financial data for political ends.

The Mysterious Shrinking Numbers: From $16 Billion a Year to Just Over $1 Billion

In a notable shift of narrative, the Governor of the Bangladesh Bank recently offered a striking revision to previously cited figures of alleged money laundering. Instead of the widely claimed $16 billion per year, he said the total amount over sixteen years might be between $18 and $20 billion. That means, on average, only about $1.13 billion was laundered per year.

This abrupt recalibration raises two pressing questions: Why did the estimated figure drop so drastically? Why does the Yunus-aligned government continue to circulate the original, highly inflated numbers?

There are three plausible explanations behind this strategic downscaling:

- Deflection from Personal and Institutional Misconduct

The exaggerated allegations of money laundering serve as a convenient distraction from Dr. Muhammad Yunus’s financial improprieties. These include funds allegedly transferred abroad under his name and the banner of the Grameen Trust, as well as substantial sums funnelled from Grameenphone and other affiliated organizations. Additionally, a web of corruption among key coordinators and allies—totalling billions—has also come under scrutiny. - Manufacturing Sympathy Through Association

By loosely associating Tulip Siddiq and the Awami League with international money laundering, the current administration seeks to blur the distinction between isolated allegations and systemic misconduct. This tactic appears aimed at garnering international sympathy while simultaneously casting doubt on the legitimacy of Sheikh Hasina’s leadership and foreign relationships. - Undermining a Development Legacy

Finally, this campaign seems to be a calculated effort to tarnish Sheikh Hasina’s development record. With Bangladesh witnessing significant growth in sectors like infrastructure, energy, and export earnings during her tenure, the spread of inflated corruption narratives appears designed to cloud public memory and distract from these concrete achievements.

The Channels of Alleged Money Laundering

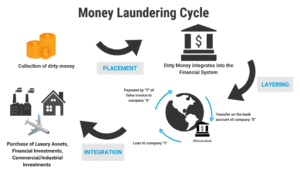

In the context of financial outflows, there are three primary channels through which money is typically laundered abroad:

- Trade-based money laundering through misinvoicing,

- Financial irregularities within large-scale infrastructure projects, and

- Illicit transfers via drug trafficking and other unlawful activities.

During Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s administration, critics have repeatedly sought to associate these mechanisms with her government, particularly by linking the decline in foreign exchange reserves to alleged money laundering.

During Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s administration, critics have repeatedly sought to associate these mechanisms with her government, particularly by linking the decline in foreign exchange reserves to alleged money laundering.

Even the Bangladesh Bank Governor acknowledged in a televised discussion with journalist Khalid Mahmood that a reduction in foreign currency reserves may, in some cases, suggest over- or under-invoicing in international trade—an established route for capital flight.

A parallel narrative has also emerged around the rise in non-performing loans (NPLs) within the banking sector, with allegations that such defaults have facilitated illicit fund transfers abroad. Notably, S. Alam Group has been repeatedly cited in this context.

These claims, however, warrant closer scrutiny. Is every fluctuation in foreign reserves to be construed as definitive evidence of money laundering? To what extent have defaulted loans contributed to cross-border capital flight? And how significant is the revised estimate of $1.13 billion annually when compared to the previously circulated—yet highly implausible—claim of $20 billion allegedly laundered over merely ten months under the stewardship of Muhammad Yunus?

Such questions must be addressed with empirical evidence and economic rigour, not political conjecture.

Interpreting Foreign Reserve Data: Myth vs. Reality

To assess the validity of the money laundering accusations, it is essential to turn to empirical evidence. This section analyzes relevant datasets sourced from Bangladesh Bank, Bloomberg, Trading Economics, and other recognized financial platforms to evaluate whether the decline in foreign reserves can be interpreted as evidence of illicit financial activity.

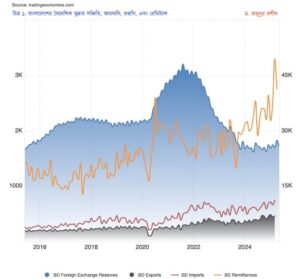

Exhibit 1, specifically the shaded blue area, highlights that Bangladesh’s foreign reserves (measured by the gross method) reached a historic high of $48.1 billion in August 2021. This occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, when international trade had slowed drastically, and global economies were experiencing significant contraction. From the following month onward, reserves began a downward trajectory.

By February 2022, coinciding with the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war, reserves had dropped to $45.9 billion. For an import-reliant economy such as Bangladesh, the compounded impact of these twin crises severely constrained the ability to maintain high reserve levels. Export volumes declined, while import costs surged globally.

By May 2024, reserves bottomed out at $24.2 billion, marking the lowest point in Bangladesh’s recorded history. Encouragingly, by June 2024, reserves rebounded to $26.7 billion, surpassing the $25.8 billion mark reported in May 2025 under the Yunus administration.

Exhibit 1 also depicts a spike in remittance inflows between April and July 2020, peaking at $2.6 billion. This sharply bolstered reserve levels. Additional indicators, such as import expenses (red line) and export earnings (black shaded area), further contextualize the balance of payments. Ultimately, the reserve position is a function of the differential between export revenues and import expenditures.

As import costs escalated due to the global crisis, the reserve decline was predictable. The Awami League government, recognizing the pressure, began implementing import restrictions in June 2022 to stabilize the situation. This policy displeased some Western stakeholders, culminating in what many consider a manufactured dollar shortage. Despite these headwinds, the government continued to promote exports. Nevertheless, foreign-backed extremist violence contributed to the fall of the Awami League administration, undermining otherwise sound economic stewardship.

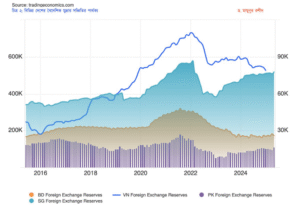

To refute the claim made by Bangladesh Bank Governor Ahsan Mansur—that declining reserves prove financial misconduct under Sheikh Hasina’s government—we must examine reserve trends in comparable economies, presented in Exhibit 2.

In January 2022, Vietnam’s reserves reached $110 billion; Singapore’s peaked in February 2022 at 579 billion Singapore dollars. Bangladesh’s apex was $48.1 billion in August 2021, and Pakistan reached a maximum of $27.1 billion in the same month.

One year later, the global economic repercussions of the pandemic and the war resulted in:

- Vietnam’s reserves declined to $86.4 billion (a $23.2 billion drop),

- Singapore’s reserves dropped $136 billion,

- Bangladesh’s reserves declined to $39.1 billion (a $9 billion drop), and

- Pakistan’s reserves declined to $14.2 billion (a $12.9 billion reduction).

Is it credible, therefore, to suggest that the Vietnamese or Singaporean governments embezzled these funds? No reputable institution supports such interpretations. Those perpetuating such claims are either misinformed or engaging in deliberate disinformation campaigns—often to conceal questionable personal wealth, including assets like Dubai properties worth 450 million taka or the alleged siphoning of $20 billion from Bangladesh in just ten months.

A Misrepresented Strength

This brings us to the second core argument: Why has there been a consistent growth in the economy? One of Sheikh Hasina’s major economic achievements was maintaining a robust equilibrium between imports, exports, and reserves.

In general, reserve levels track closely with export earnings. Consider Vietnam’s case—reserves stood at $110 billion in January 2022 against 2021 exports of $336.31 billion, yielding a reserve-to-export ratio of 0.33. By contrast, Bangladesh under Sheikh Hasina had reserves of $48.1 billion in August 2021 against exports of $38.86 billion, resulting in a ratio of 1.24. This suggests a far superior efficiency in reserve accumulation compared to Vietnam.

Nevertheless, this success story was weaponized through public misinformation and politicized narratives, turning a strength into a perceived liability in the public eye.

Corruption in Mega Projects? A Closer Examination:

The oft-repeated allegations of corruption tied to Bangladesh’s mega infrastructure projects—particularly under the Awami League government—do not stand up to scrutiny. Two prominent cases serve to illustrate this.

First, the power distribution agreements between the Government of Bangladesh and India’s Adani Group came under intense criticism, with detractors claiming large-scale corruption and accusing the government of compromising national interests. However, these claims were later found to be unsubstantiated. Notably, despite earlier promises, the current Yunus administration has not cancelled a single major bilateral project with India or other international partners—an implicit acknowledgement of their legitimacy.

Second, allegations of multibillion-dollar graft involving the Ruppur Nuclear Power Plant and British MP Tulip Siddiq gained traction through social media and partisan outlets. Yet, when calls for evidence emerged, those promoting the claims failed to substantiate them. The narrative swiftly shifted, and with it, the scale of the accusations. As a result, the original claim of $16 billion laundered per year was quietly downgraded to a total of $18 billion over 16 years.

Such inconsistencies have eroded credibility to the extent that even international actors—including the UK government—have distanced themselves from individuals previously championed as global anti-corruption advocates.

When broken down, this revised figure of $18 billion over 16 years equates to approximately $1.13 billion annually—a dramatic reduction that calls into question the motives behind the earlier, inflated claims.

Let me show you a humorous comparison next.

Is Reserve Loss Through International Banking Evidence of Corruption?

A foundational aspect of global trade is the correspondent banking system, which enables countries—Bangladesh included—to settle import-export transactions through foreign banks. This system necessitates maintaining U.S. dollar or other foreign currency balances abroad. These balances are routinely “topped up” to meet payment obligations, and countries sometimes resort to short-term borrowing to ensure smooth transaction settlements.

Fluctuations in foreign exchange rates, combined with varying clearing requirements, often result in countries depositing additional funds to avoid settlement delays. According to international estimates, low- and middle-income countries incur average annual losses of approximately $1.98 billion due to such routine currency fluctuations and clearing inefficiencies.

This raises a critical question: if these countries are regularly losing close to $2 billion annually due to systemic banking mechanisms, can Bangladesh’s recalibrated figure of $1.13 billion per year—framed as “corruption” by critics—reasonably be considered exceptional or criminal? Or is this, in fact, a normative outcome of operating within global financial systems?

Loan Defaults and the Money Laundering Narrative

Another pillar of the corruption narrative involves accusations that individuals and institutions allegedly aligned with Sheikh Hasina’s administration defaulted on loans and subsequently laundered funds abroad. The S. Alam Group has been the most frequently cited example.

Before assessing the merit of these claims, let us turn to Exhibit 3, which presents recent data on non-performing loans (NPLs) in Bangladesh.

The findings highlight a critical fact: if the total volume of bad loans accumulated in Bangladesh from independence to December 2024 is represented as 100 units, then 60 of those units were incurred over the 53 years up to June 2024—while the remaining 40 units emerged in just the six months from July to December 2024.

This exponential rise in NPLs within such a short timeframe coincides with a period of intense political and economic turmoil, notably the Yunus-backed July uprising. During this unrest, widespread arson attacks destroyed factories and workplaces, leading to the loss of livelihoods for over two million workers.

Even if one discounts the role of political violence in exacerbating loan defaults—a highly improbable stance—is it intellectually honest to blame a 54-year accumulation of bad loans solely on the previous administration, while ignoring the unprecedented 40% surge under the current regime’s six-month tenure?

Is it not fair to ask whether the dramatic increase in NPLs was, in part, due to fund diversion and possible money laundering by actors aligned with the current administration?

Furthermore, such selective indignation appears especially hollow in light of past events: Tarique Rahman—formally indicted by the FBI—was implicated in laundering over Tk 20,000 crore from Bangladesh to eight countries between 2004 and 2005. Despite these serious charges, he currently enjoys impunity.

Why Is S. Alam Group Being Targeted?

Among the recent financial controversies, the case receiving the most media attention has been the alleged foreign investment of Tk 10,000 crore by S. Alam Group. However, few have critically examined the actual asset base—both tangible and intangible—of the group within Bangladesh. Its enterprises remain fully operational and profitable.

Ironically, many leaders of the newly formed National Citizen Party (NCP), backed by Dr. Yunus, now enjoy the benefits of high-end vehicles and extravagant iftar meals costing $100 per plate—reportedly financed by donations linked to the very institutions they now accuse of misconduct.

So, why is S. Alam Group the particular focus of this media campaign?

The answer appears to be political rather than economic. When S. Alam Group acquired majority control of Islami Bank Bangladesh Ltd, it effectively dismantled Jamaat-e-Islami’s longstanding grip over the country’s first major Sharia-compliant financial institution.

To recall the context:

- Islami Bank was established in 1983 during the regime of General Ershad and served as the Jamaat-e-Islami’s key financial platform in Bangladesh.

- After the assassination of President Ziaur Rahman, Ershad facilitated the Jamaat’s alignment with Middle Eastern countries, expanding manpower export and Hajj-related enterprises, creating a significant revenue stream.

- Islami Bank functioned as the Jamaat’s financial backbone, enabling political rehabilitation and ideological expansion.

Losing this institutional control to S. Alam was a major setback for Jamaat-e-Islami, both politically and economically. The ensuing backlash—manifested as targeted allegations and media narratives—appears to be an extension of that loss.

Otherwise, it is difficult to explain why individuals such as PK Halder, who defaulted on loans exceeding Tk 3,000 crore, have been quietly released from prison under the current Yunus-backed administration.

Meanwhile, Islamist financial networks, with connections in Malaysia, Turkey, Qatar, and the UK, have allegedly laundered substantial sums under the guise of foreign investment. In this context, the public narrative against S. Alam Group appears less about financial irregularities and more about political retaliation and diversion.

Conclusion

In summary, the sweeping allegations of money laundering levelled against Sheikh Hasina and her family remain unsubstantiated by any credible evidence. Rather, what appears to be unfolding is a calculated media campaign—engineered to inflict political damage on the Awami League after repeated failures to unseat them through electoral or democratic means.

Meanwhile, the staggering financial irregularities involving Yunus-backed NCP leaders, the long-standing extortion networks run by Jamaat-e-Islami, the near-collapse of Bangladesh’s banking and capital markets, and the illicit outflow of an estimated $20 billion within just ten months have all been carefully obscured from mainstream discourse.

Consider this: despite the banking sector already holding Tk 1.4 trillion in surplus liquidity, the current regime printed an additional Tk 225 billion to bail out six struggling banks, four of which were Islamic banks. This move allowed these institutions to access interest-free liquidity, bypassing market mechanisms and avoiding normal deposit costs.

When public resources are deployed in such a targeted and opaque manner—favouring specific institutions or political interests without competitive or regulatory justification—it is nothing short of institutionalized corruption.

Who will be held accountable for this?

Moreover, suppose a financial institution claiming to operate under Islamic principles must rely on printed fiat currency to sustain itself. In that case, it begs the question: how “Islamic” is its financial model in practice?

This is not to suggest that corruption did not exist under the Awami League. Realistically, large-scale economic development in any emerging economy often comes with inefficiencies and a degree of corruption. These are structural challenges, not moral absolutes.

But it is worth asking: who are the critics? Those who accuse others of corruption while themselves presiding over the sale of arms, instigating wars, toppling governments, and overseeing mass casualties across the globe. In that context, the accusations levelled against Sheikh Hasina appear both hypocritical and politically motivated.

Today, global institutions bestow Nobel Peace Prizes on individuals and organizations whose actions often align with geopolitical interests that undermine peace and justice. The very actors who champion “anti-corruption” narratives frequently do so while suppressing dissent through media censorship, violence, and covert political engineering.

In contrast, Sheikh Hasina, a leader who has survived 19 assassination attempts, achieved one of the rare economic feats among developing nations: generating $48.1 billion in foreign reserves from $38.86 billion in export earnings—a reserve-to-export ratio of 1.24, unmatched by peer economies like Vietnam.

How many of us have even paused to acknowledge this?

What more must a leader accomplish to satisfy a segment of the population and international community who now, ironically, fear stepping outside, not due to instability under her governance, but the very forces that replaced her?

Comments (0)