The interim government’s ban on Bangladesh’s largest political party undermines democracy, empowers extremists, and threatens…

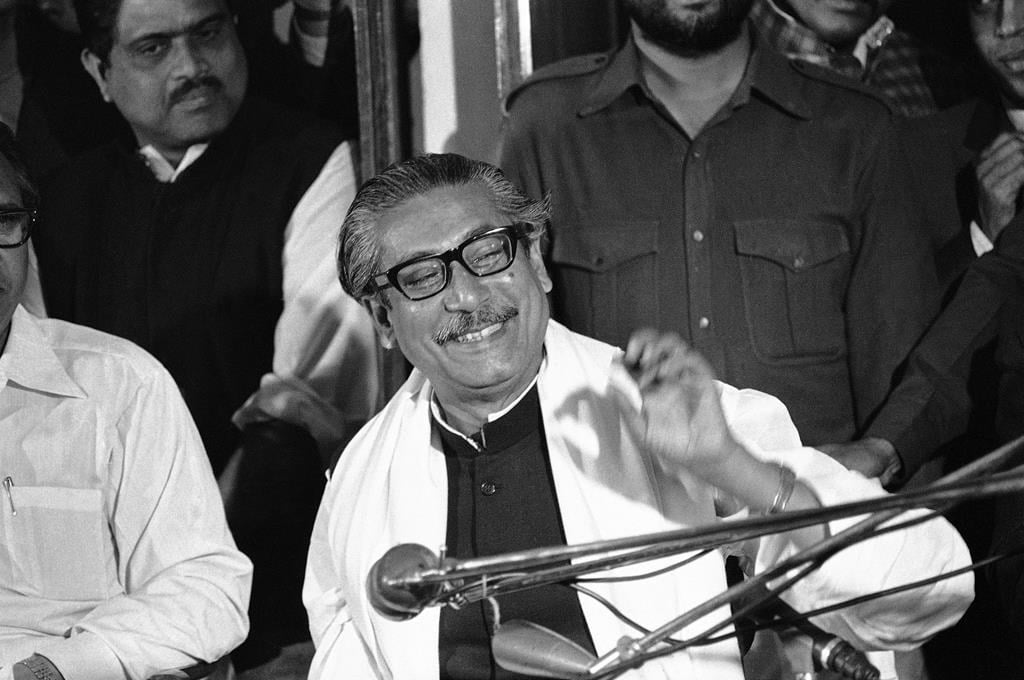

My Memories of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib and Encounters with History

Manirul Islam

I write these reflections to share my personal memories of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, encountered within the intimacy of family life. I will also weave in the broader political tapestry of the time, along with conversations. I believe these fragments offer a unique lens through which to understand the enduring historical significance and global resonance of the name Sheikh Mujib.

I was fortunate to meet Bangabandhu twice, each time in a family setting. Beyond these meetings, I had countless discussions about Bangladesh with colleagues, friends, distant acquaintances and even strangers. This was the pre-Internet era, a time when anyone who knew of Bangladesh would invariably mention one name: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the Father of the Nation. And without fail, their next question was always tinged with frustration and anguish: “Why did you kill him?”

The political journey began in 1949 with the formation of the East Pakistan Awami Muslim League (later the Awami League in 1953) by Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani, Yar Mohammad Khan, Shamsul Huq, and the young activist Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, later joined by Hussein Shaheed Suhrawardy. It was founded as a democratic alternative to the dominating Muslim League. My maternal grandfather, Advocate Kazi Mozaffar Hossain, was its founding Chairman, a role he assumed at Sheikh Mujib’s initiative (Osomampto Atmojiboni p125). Throughout this period, including the pivotal events of February 21, 1952, Sheikh Mujib was frequently in and out of prison until his release in early 1953.

The Pakistan government then announced the first legislative elections for East Bengal since its independence. In response, the opposition Juktofront (United Front) alliance was formed between the Awami League and the Krishak Sramik Party to challenge the Muslim League. A vigorous campaign swept across East Bengal (not yet officially renamed East Pakistan) in 1953, led by Haque, Bhasani, Suhrawardy, and the young, lanky, and energetic Sheikh Mujib.

It was during this fervent campaign that a small family story became part of history. In February 1953, my elder sister Selina was born at my grandfather’s (Nana’s) house. As the first grandchild, she was the center of my grandmother’s (Nani) world. When Haq, Bhasani, and Suhrawardy were scheduled to visit Gopalganj for a rally, my Nana, as local party chair, volunteered to host them.

Overwhelmed with preparations, my Nani lamented to Sheikh Mujib when he came to check on the arrangements, “Mojibor, because of your party, I am neglecting my first grandchild.”

Sheikh Mujib replied with firm affection, “Bubu (elder sister), listen. One day, I shall be the Prime Minister of this country. Then I shall take your granddaughter (Natni) to make tea for me.”

The 1954 provincial election delivered a landslide victory for the Juktofront, which won 223 of 309 seats. The Muslim League Chief Minister, Nurul Amin, and his entire cabinet were defeated. The result sent an unmistakable message to the federal center—a message they tragically misconstrued, setting the nation on a path to its inevitable destiny.

Years later, amid massive political upheaval, power was handed from one military junta to another on March 25, 1969, when Ayub Khan yielded to General Yahya Khan. President Yahya announced a national assembly election for October 5, 1970, ostensibly to restore democracy. The date was later postponed to December 7, officially due to monsoon floods, though critics argued the true motive was to break the Awami League’s undeniable momentum.

Then, on November 8, 1970, the catastrophic Bhola cyclone struck. The government’s callous response to the suffering millions became a final catalyst for the election. While all other parties called for another postponement, Bangabandhu—the title “Friend of Bengal” bestowed upon him by the people—stood alone. At a press conference, he warned that frustrating the polls would force the people to “make the supreme sacrifice of another million lives, if need be, so that we can live as a free people.” President Yahya agreed to defer elections only in the seven worst-hit constituencies, holding firm on the December 7 date for the rest.

We were living in my father’s workplace, Mathbaria, one of the postponed areas. In that constituency, conventional wisdom predicted a close race between the National Awami Party and the Muslim League, with the Awami League candidate a distant third.

The results from the rest of the country shattered all predictions. The people of East Pakistan delivered a resounding victory to the Awami League, making it the single largest party in the assembly. Now, Bangabandhu turned his attention to the remaining southern seats. When he came to Mathbaria, a crowd of unprecedented size gathered to hear his thunderous voice and clarion call for support. The shift in the public mood was palpable.

After the rally, during a meeting with local leaders, the Secretary of Mathbaria Awami League mentioned that the eldest daughter of Advocate Mozaffar Hossain—my mother—was in town. Bangabandhu expressed a desire to visit our home.

He arrived, and a crowd filled our large front lawn. He had to bow deeply to enter our front door, then turned and instructed everyone to stay outside. When Bangabandhu entered the living room, the very air seemed to change. He was tall, dignified, and radiated a gentle strength. He moved among us not as a distant statesman, but as a beloved guardian. His trademark white panjabi, dark Mujib coat, and simple spectacles spoke of humility, yet his presence was utterly magnetic.

We customarily touched his feet for his blessing. As my mother introduced each of us, she came to my elder sister. “Mama (Uncle), this is my eldest daughter. During the 1953 election, you saw her when she was just a few months old”.

“Yes, I remember,” Bangabandhu replied. He looked at my sister and said, “The people of this country have chosen me to be their Prime Minister. Now, as I promised your Nani, I shall take you to make tea for me.” My mother was speechless. “Mama,” she finally exclaimed, “do you still remember that comment from so long ago?” “I didn’t forget,” he replied simply. When introducing me, my mother complained, “Mama, my only son studies less and is more engaged in politics.” Bangabandhu looked at me and said, “Vai (brother), this is the time to study. For politics, there is plenty of time ahead.”

The second meeting was in the winter of 1972 at my uncle’s wedding at the Dhaka Ladies Club. Many political figures were present. As Bangabandhu moved through the pitched tent, greeting everyone with his deep, resonant voice, the boundary between the leader and the commoner dissolved. He listened with genuine, undivided attention as my family discussed everything from family matters to Gopalganj politics in their local dialect.

Suddenly, he gestured for me to come closer. He placed his hand on my shoulder and asked my mother, “Shamsun Nahar, isn’t this your only son?” Then he asked me, “How are your studies?” Before I could answer, my mother interjected with great enthusiasm, “Mama, *mashallah*, he achieved an extraordinary result on his Secondary exam!” He bent his head, looked directly at me with a face emitting pure joy and optimism, and said in a voice deep with affection, “Vai, study well. Bangladesh needs brilliant minds like yours.” His optimism was infectious, his sharp memory legendary.

In the years that followed, I often reflected on that encounter. During moments of national crisis or personal doubt, Bangabandhu’s words echoed within me—a reminder to persevere, to cherish hope, and to place the welfare of others at the heart of every endeavour.

On August 15, 1975, as dawn broke, I woke to a loud uproar from the adjacent Sher-E-Bangla dormitory. From the fourth floor, I saw a crowd of ten to twelve people dancing with vulgar joy, screaming, “Sheikh Mujib has been killed with his entire family!” I spotted two known students from Barisal who had been Rajakars in 1971; they had once threatened me to join the campus Chatra League (Mujibbad). I returned to my room, trying to reconcile myself to this new reality. This is no longer my country, I thought. I have to leave.

I graduated in January 1978, secured my first job in Libya, and left. I was posted at the Rumyia power plant, a desolate place surrounded by rocky mountains. My nearest supply point was the mountain city of Yefrin, 15 km away along a perilous, winding road. I hitchhiked almost daily, bargaining with Libyan drivers for a ride.

One day, I was picked up by a driver in a rural Libyan outfit, with gold-plated teeth—a status symbol among nomadic tribes. He could have been a chieftain. My Libyan Arabic was still poor, but we communicated through gestures and broken words.

“Min Owen?” (Where from?) he asked, as always.

“Bangladesh,” I said.

“Bangladesh?” he asked for confirmation.

“E, Na’am.” (Yes.)

Suddenly, he fell silent. When he turned to me, his eyes and face burned with anger and hatred. I felt a spike of fear, knowing the Bedouin reputation for unpredictable moods.

“Why did you kill Sheikh Mojibar Rahman?” he retorted.

“Not me, not me,” I ardently tried to calm him.

He glared. “You are haiwan (animal). Qul Watan Haiwan (The entire nation is animals).”

I lowered my gaze and stayed silent, still scared. He drove the rest of the way in an eerie silence. At our destination, I extended my hand with payment. He gestured for me to leave the coins on the seat, refused my thanks and ‘salam’, spat out his window, and sped away.

I looked at the sky and took a deep breath. I asked myself; Did I deserve that?

I looked at the distant peaks shrouded in white cloud. I heard the resonance of a voice, “Vai, study well. Bangladesh needs brilliant minds like yours”.

I haven’t returned home since. At every border crossing, every airport immigration, every checkpoint where I faced humiliation, I assured myself: Yes, I deserve it.

The author is an Engineering Graduate from the BUET, and currently residing in Toronto, Canada.

Comments (0)